Afia was the product of our group studio project for the Master in Design Engineering, during the first year Collaborative Design Studio. I worked with a wonderful team of 4 - Julian, Kenneth and Janet.

Since our work on Afia is actually summarized and packaged nicely in the MDE Health Systems book, I'm including an excerpt of that book here, as well as a link out to the original book if you want to learn more about the studio, and other projects as well.

Here is a link out to just this excerpt if you'd prefer to read this in a native PDF reader:

file here.

Our task was to investigate potential problems broadly in the "health" space that might be realistically addressed by research and innovation.

Here's a summarized version of our project (a subset of our final presentation)-

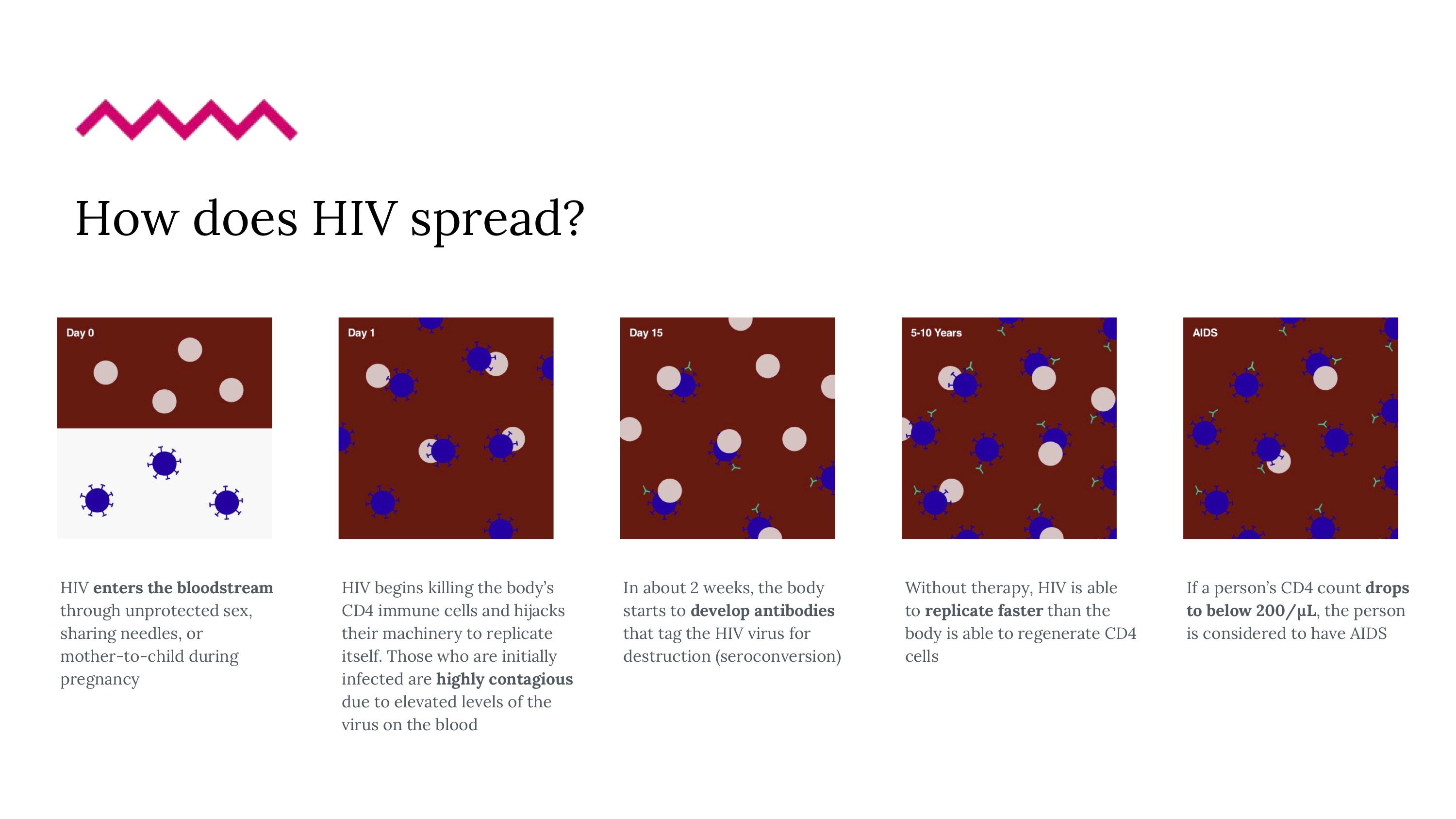

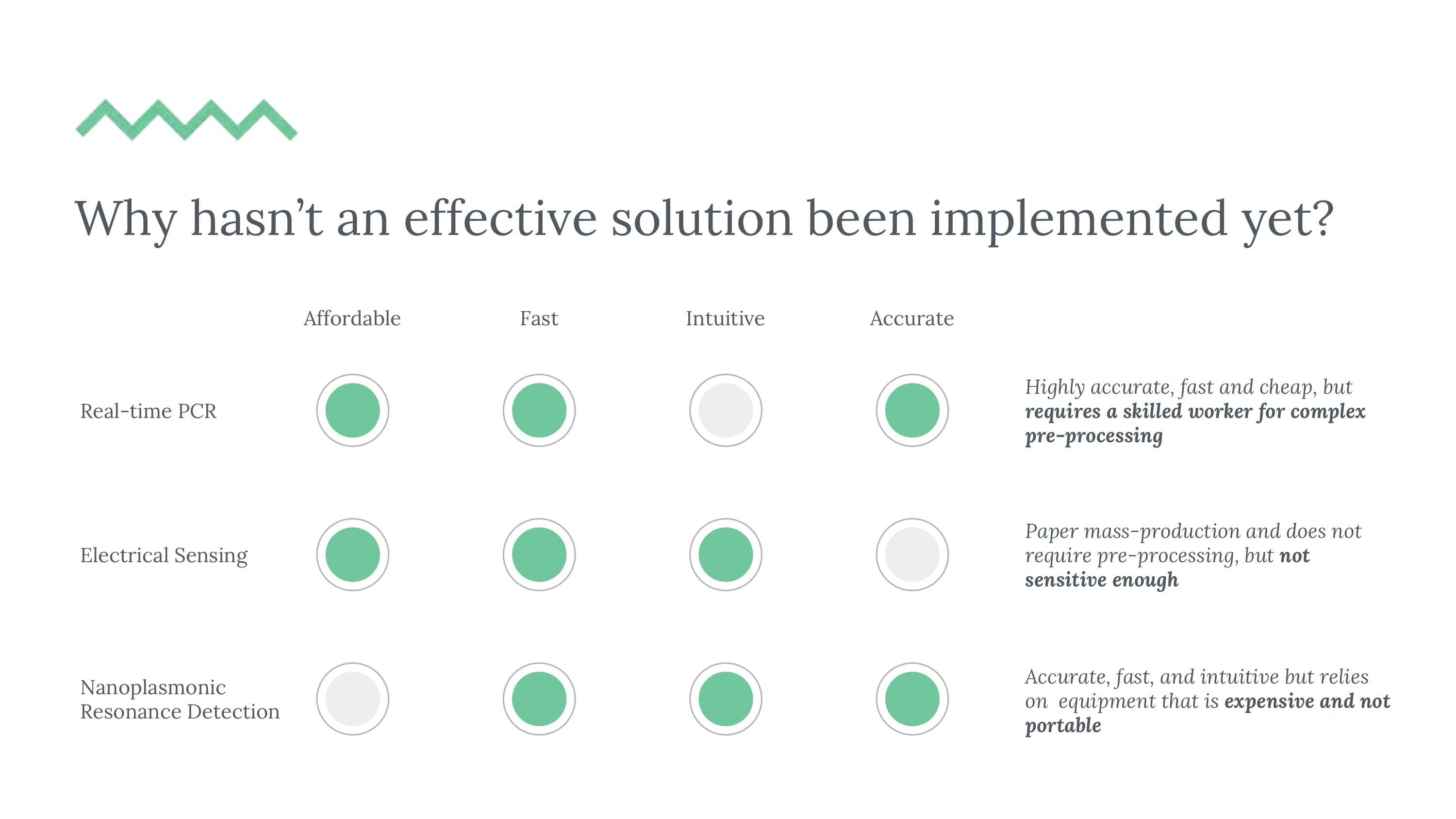

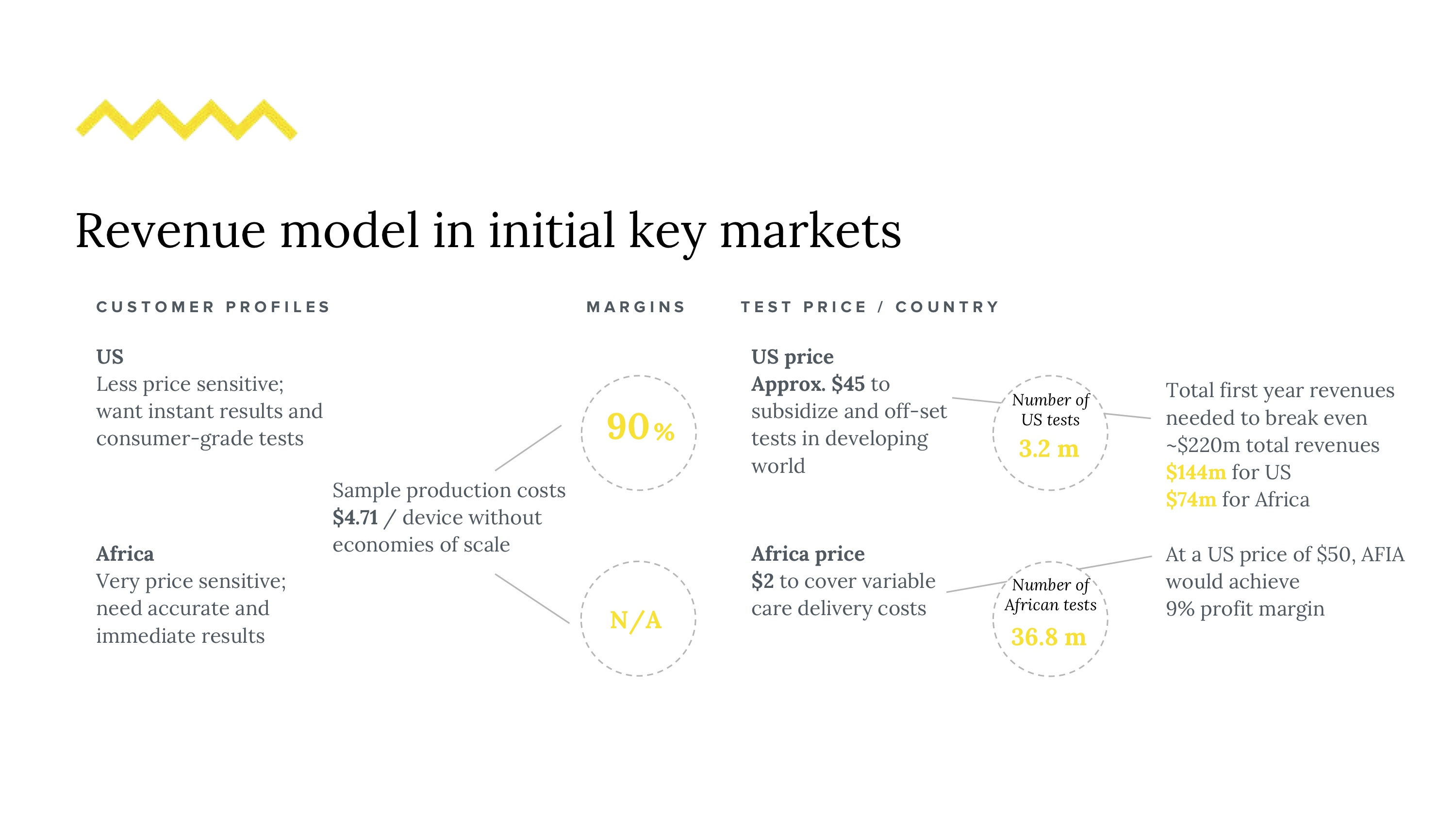

37 million people in the world have HIV - this number grows on the order of millions, annually. Attrition in testing continues to remain a problem, leading patients who enter the diagnostic pipeline to dropping out of the testing schedule before even getting a final diagnosis. We want to reduce this number by reducing detection time for potential early HIV infections. Even though testing is not to blame for the epidemic, it does play a significant role in awareness, transmission, and patient agency. Current HIV testing may lack sensitivity based on cost, is slow, and requires training, relegating it to expensive procedures often performed in labs. The need for sensitive testing is furthered by the U=U movement (undetectable = untransmittable), recently backed by the CDC. Given our market, regulatory challenges and technical requirements, a good solution is (1) simple and intuitive, (2) fast, (3) deployable and easy to use on the field, and (4) affordable. Could it be feasible to redesign this diagnostic experience?

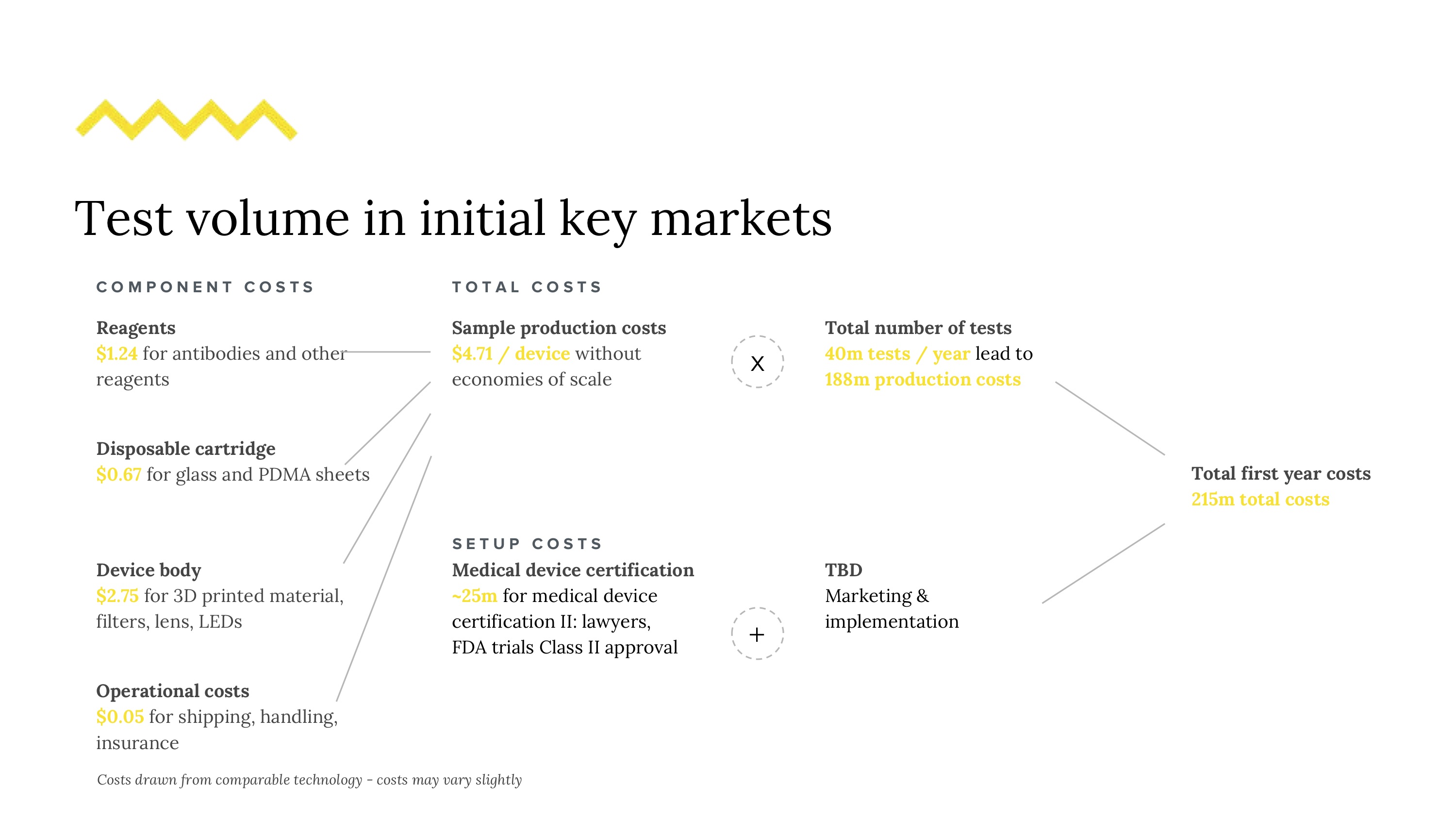

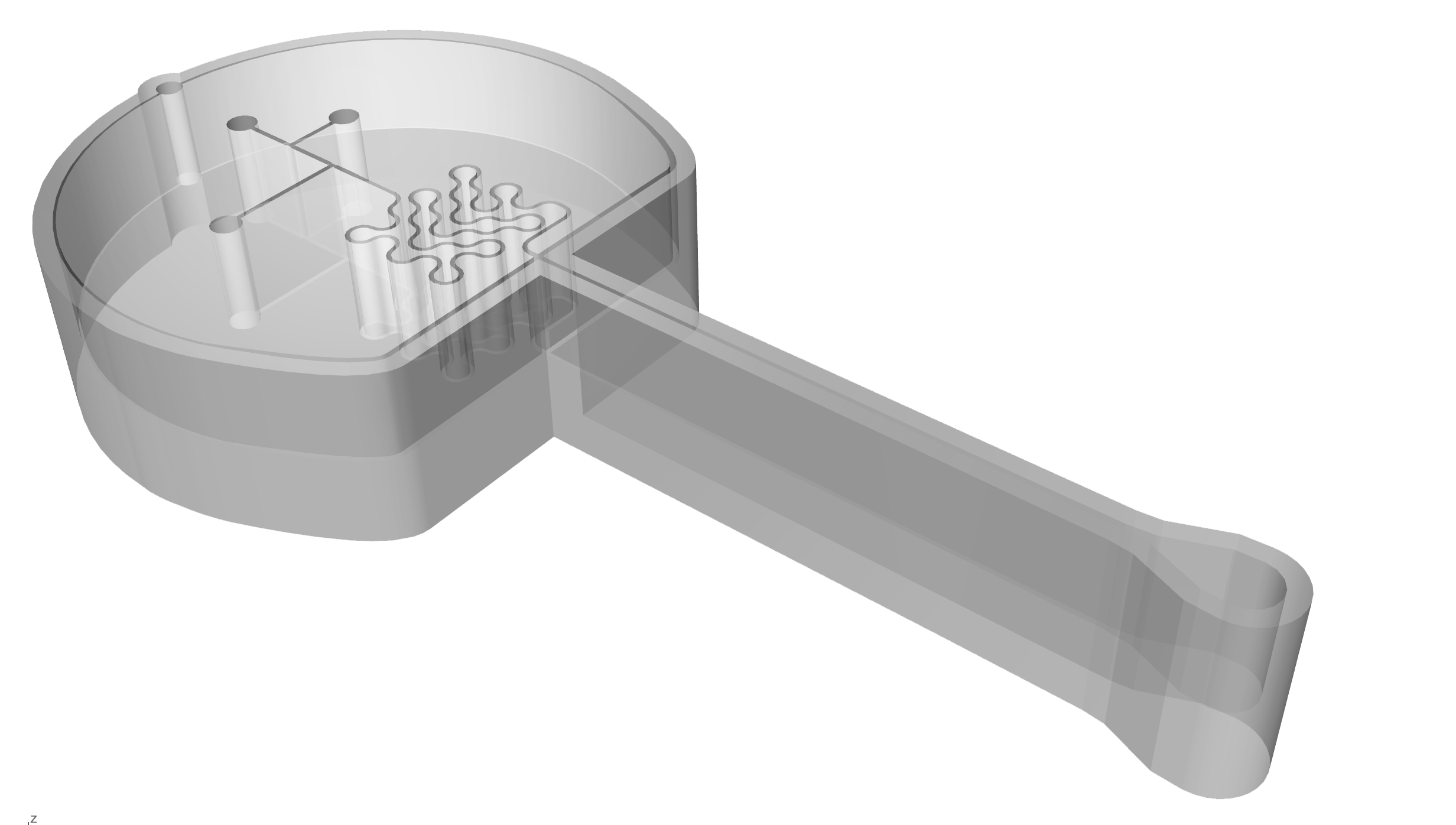

We created a speculative approach to a flow cytometry-based assay that implements microfluidic processes with the goal of safely, accurately and quickly count viral load measurements with small samples of blood. The microfluidic device would be implemented in concert with smart-phone compatible hardware and a companion app that both fits standard phone types used in regions most heavily affected by limited diagnostics and allows both in-clinic and at home usage (especially given potential on-demand reasons people may want to assess their viral loads). To circumvent the need to do testing exclusively in labs (where a lot of lag is currently introduced), we designed our device with simplicity and disposability in mind. We’ll cover our research and solution on 4 different scales: (1) the viral scale (technical interactions), (2) the device scale (components), (4) human scale (clinical, user experience), and (5) the systems scale (national rollout).

And finally, a few images of the actual work in progress-

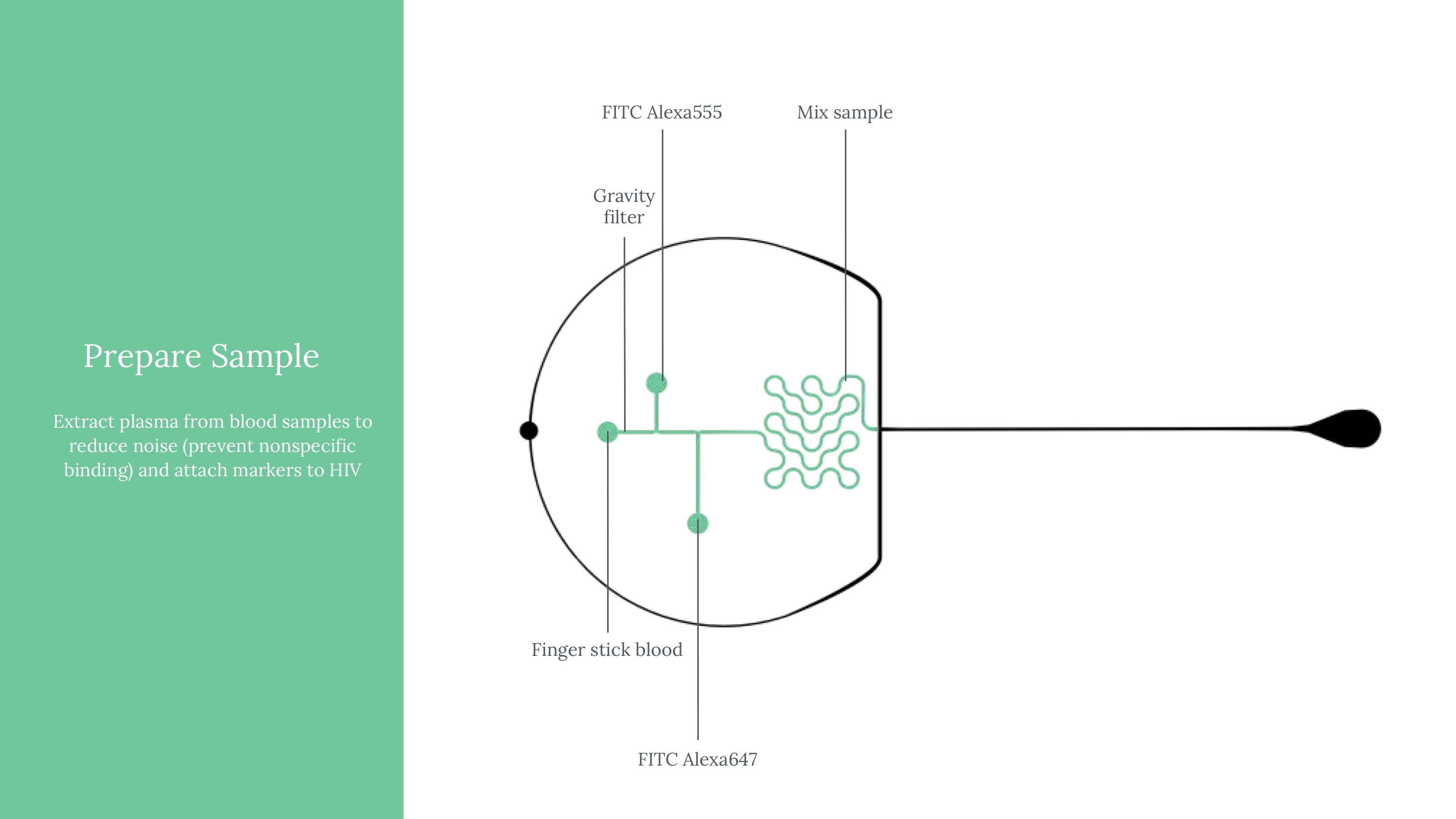

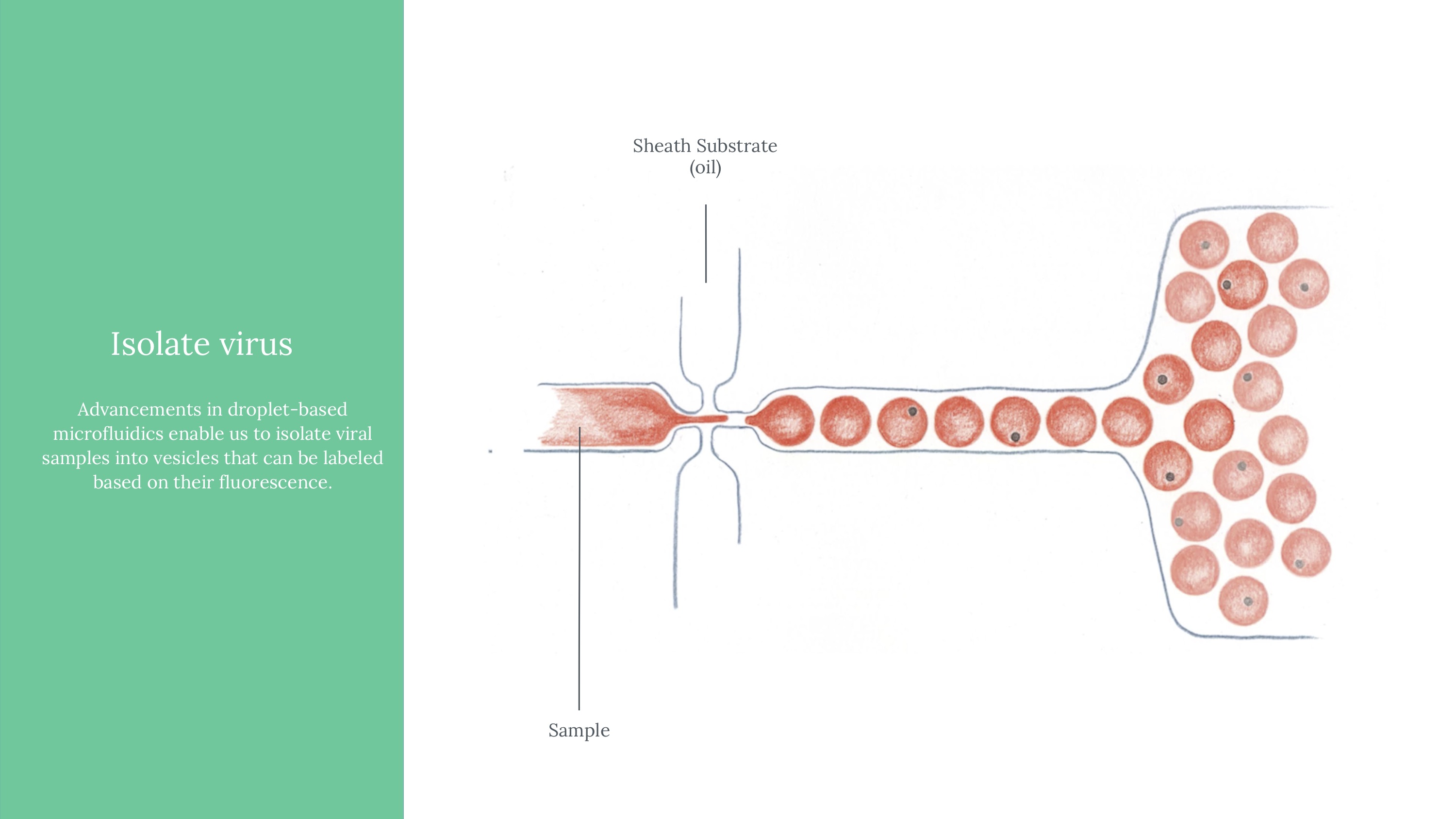

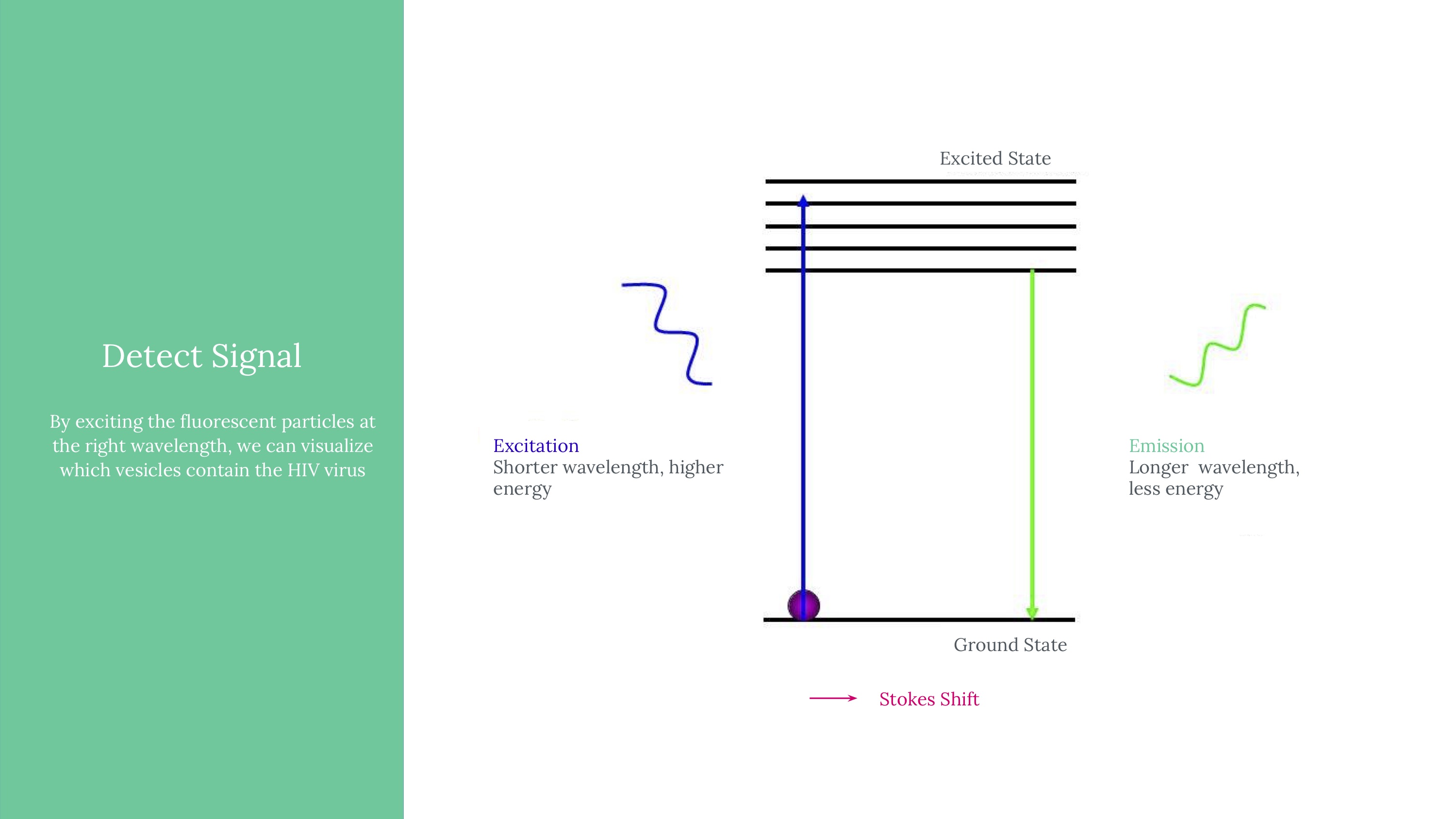

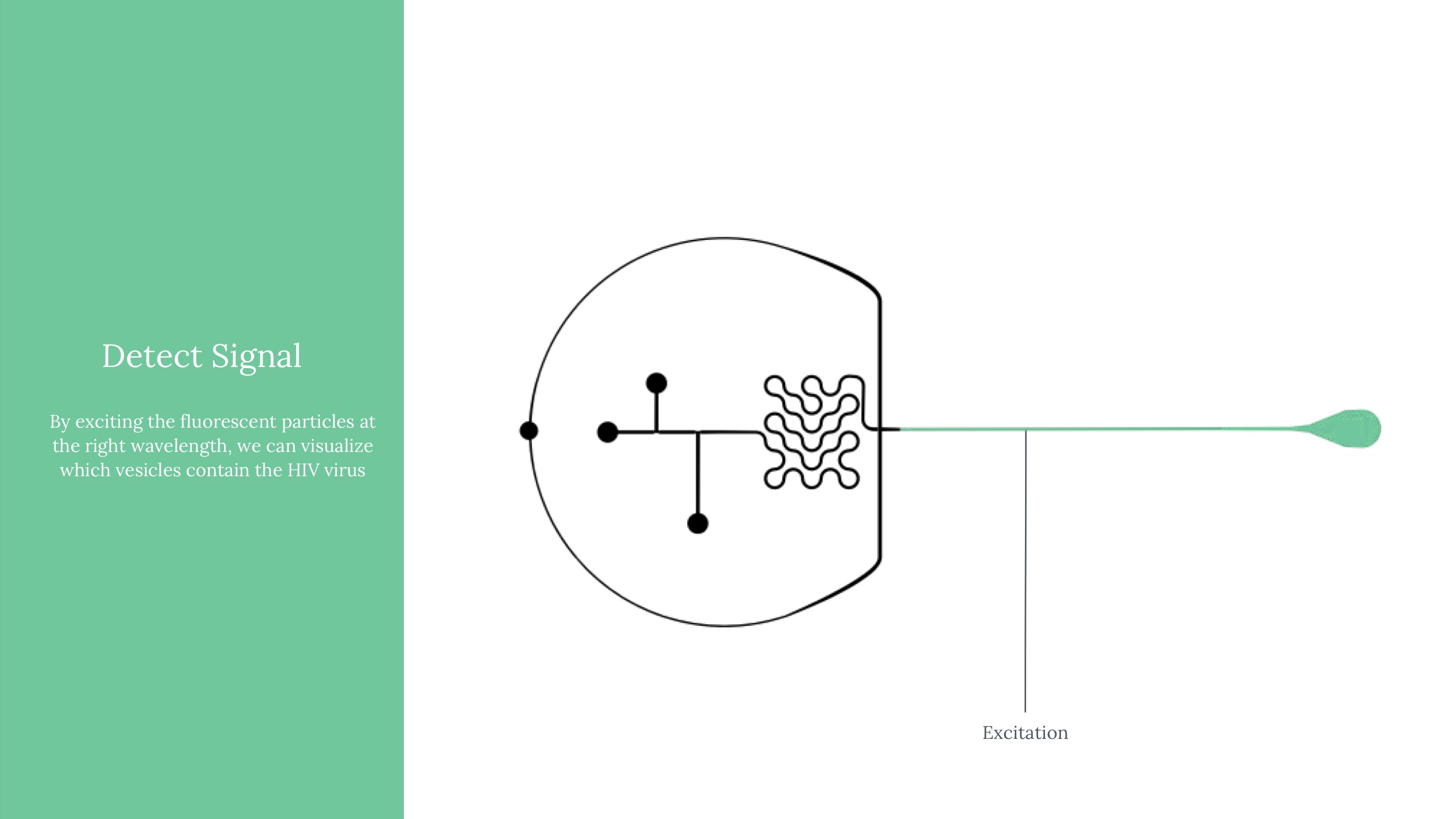

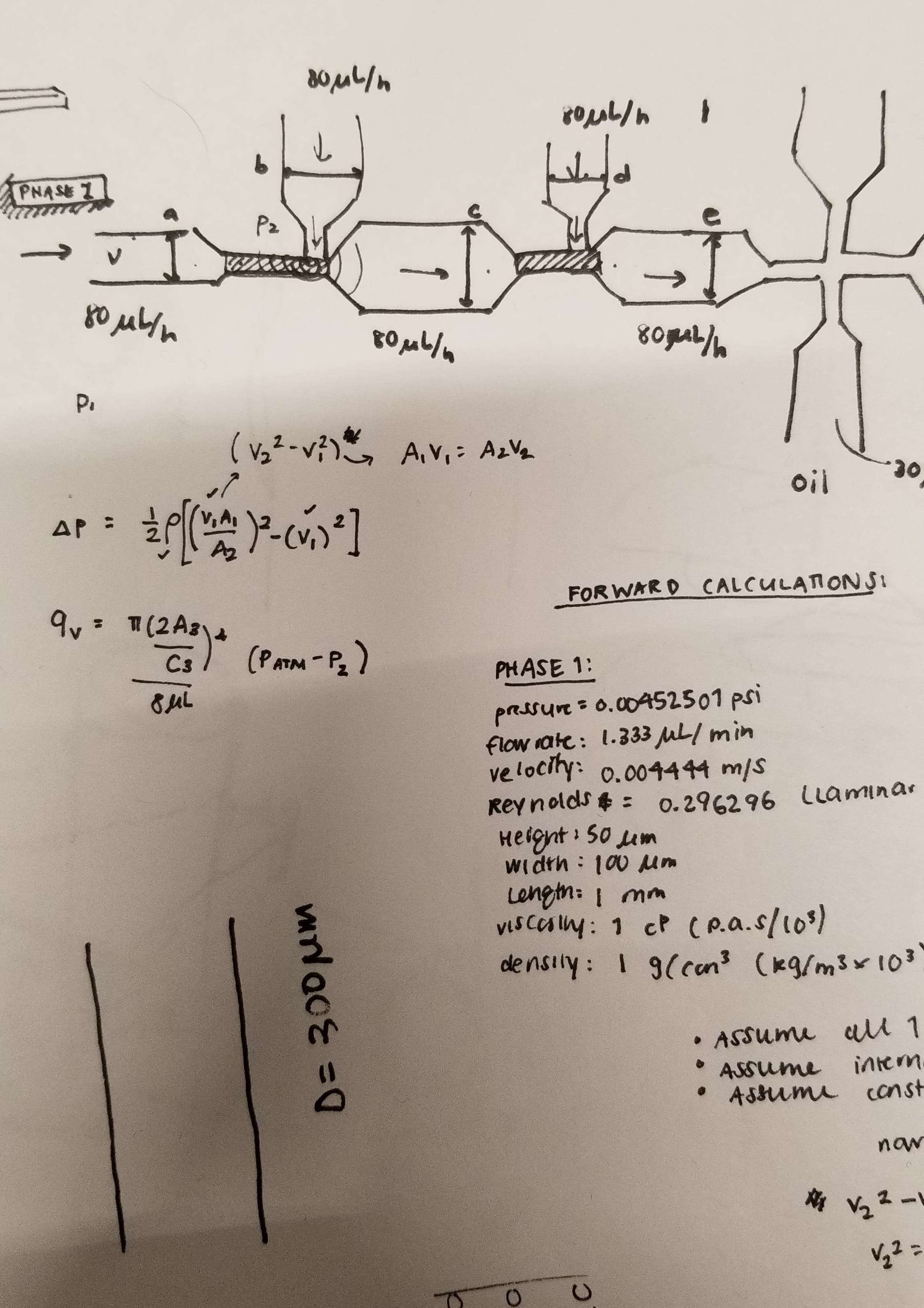

Viral load ultimately means measuring the quantity of a virus in a sample of blood. Viral load matters because it determines the transmissibility of HIV. To attempt to measure this, we ultimately used an approach of labeling HIV virus cells with a marker, guiding blood samples into thin channels that would form vescicles (bubbles containing 0 or 1 virus cells each), and then guiding those vesicles at a controlled speed through an imager to determine whether that vesicle contains a virus or not (if yes, it would flouresce). Obviously, this kind of project would need rigorous and expansive testing to see how it might perform if actually pursued.

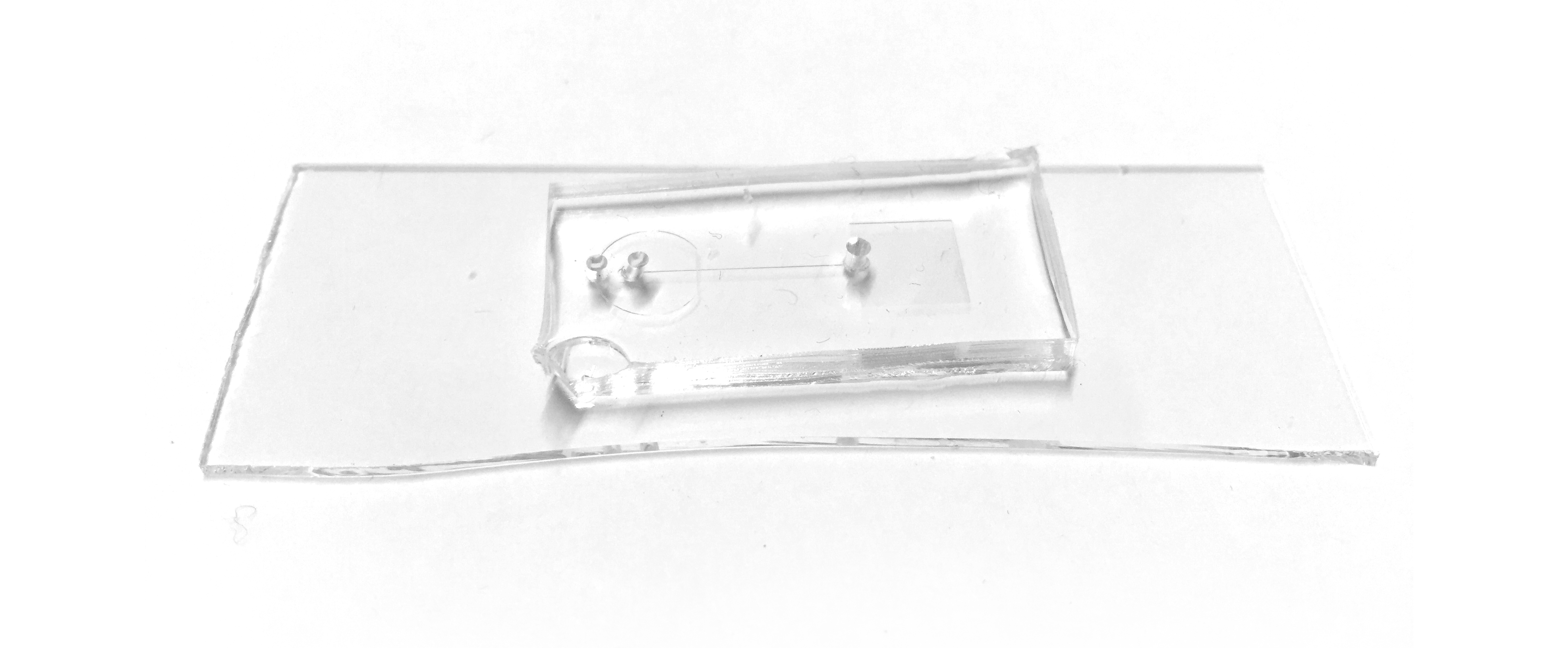

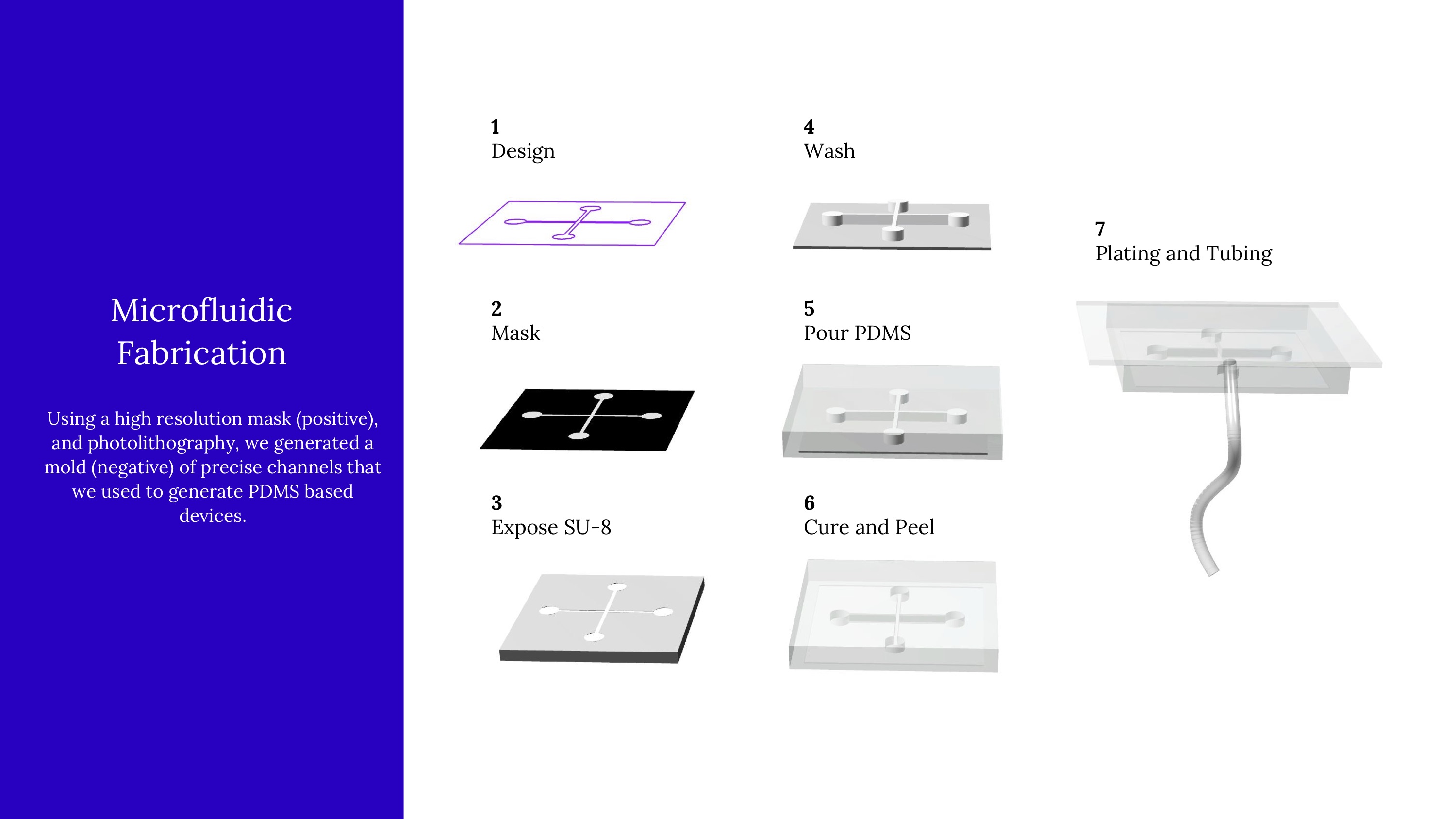

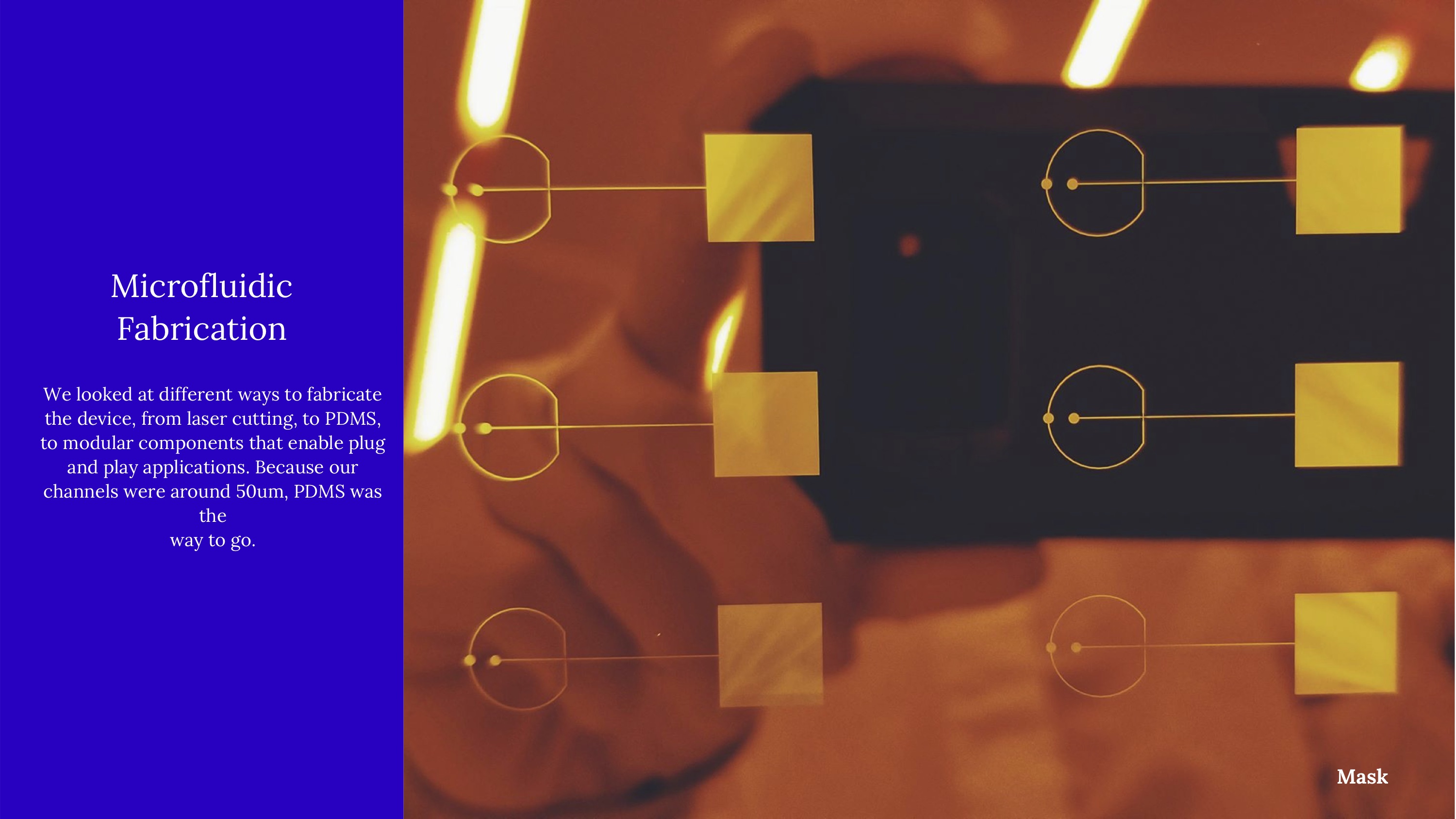

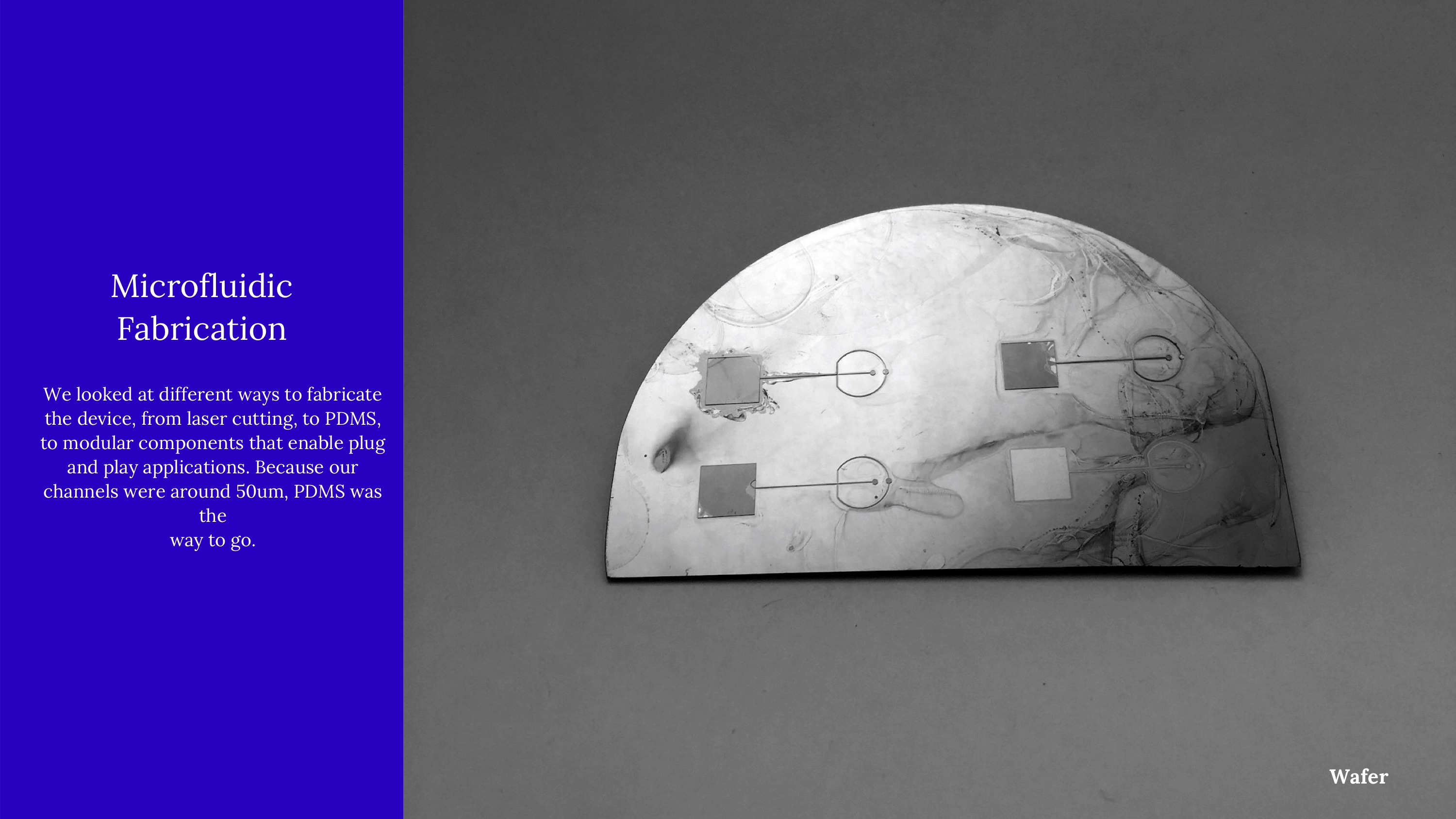

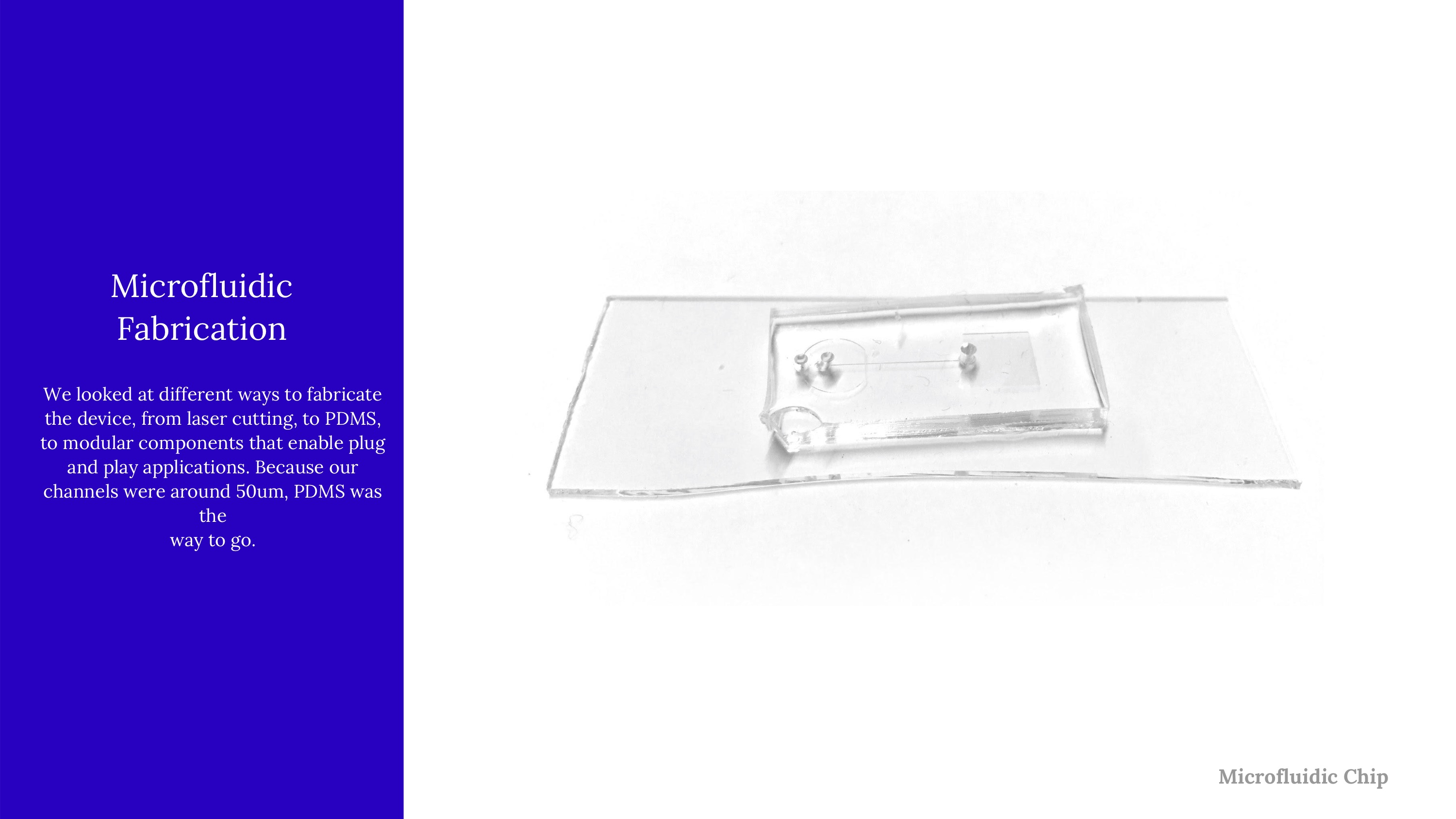

Because our microfluidic device needs to be made with positive and negative molds, we started by creating this wafer (a positive mold). It's a little hard to spot, but these wafers have high-precision channels that are slightly elevated above the surface. By pouring PDMS on top of this, the raised surface actually became a negative surface on the PDMS, etching channels into it.

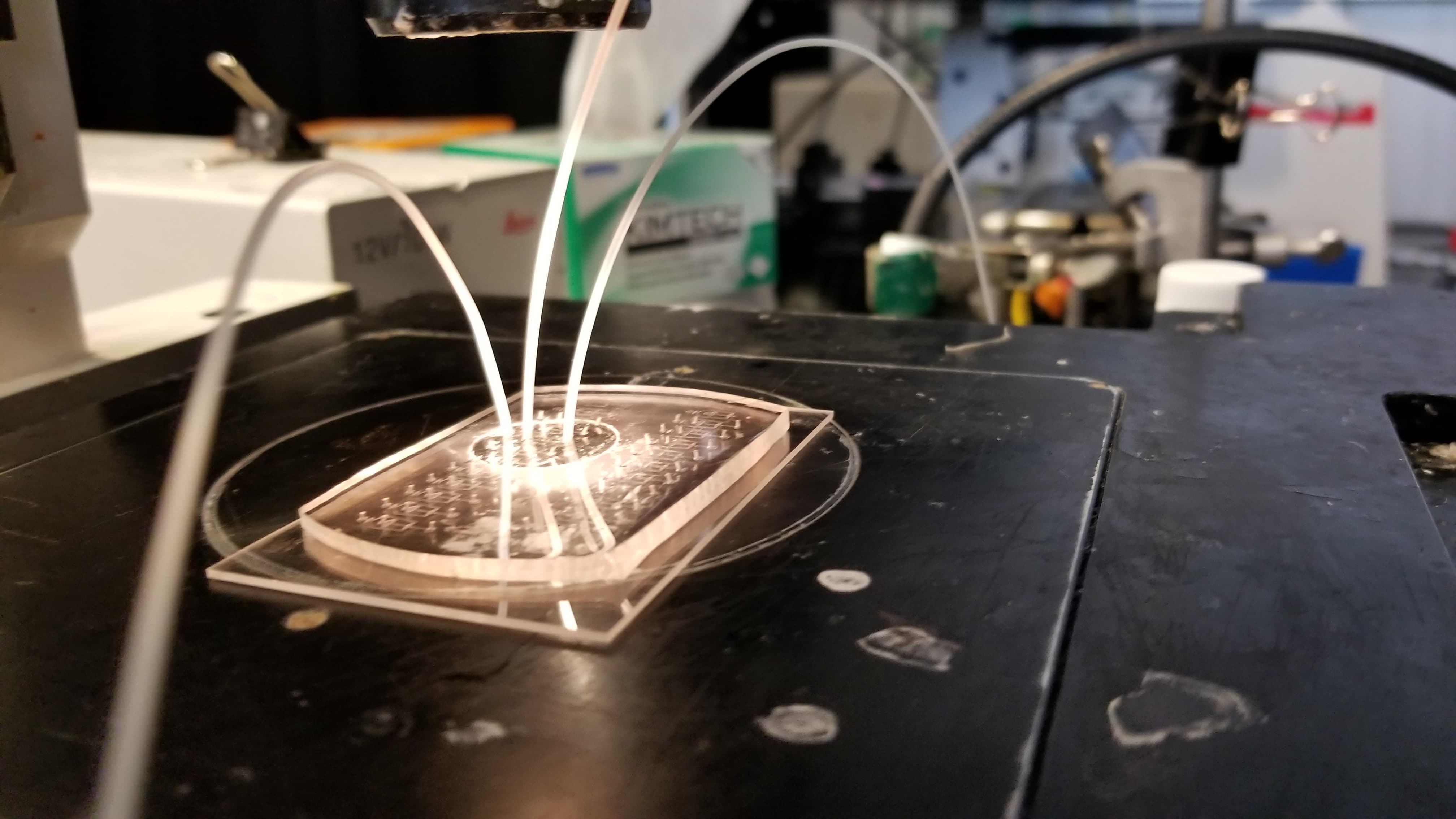

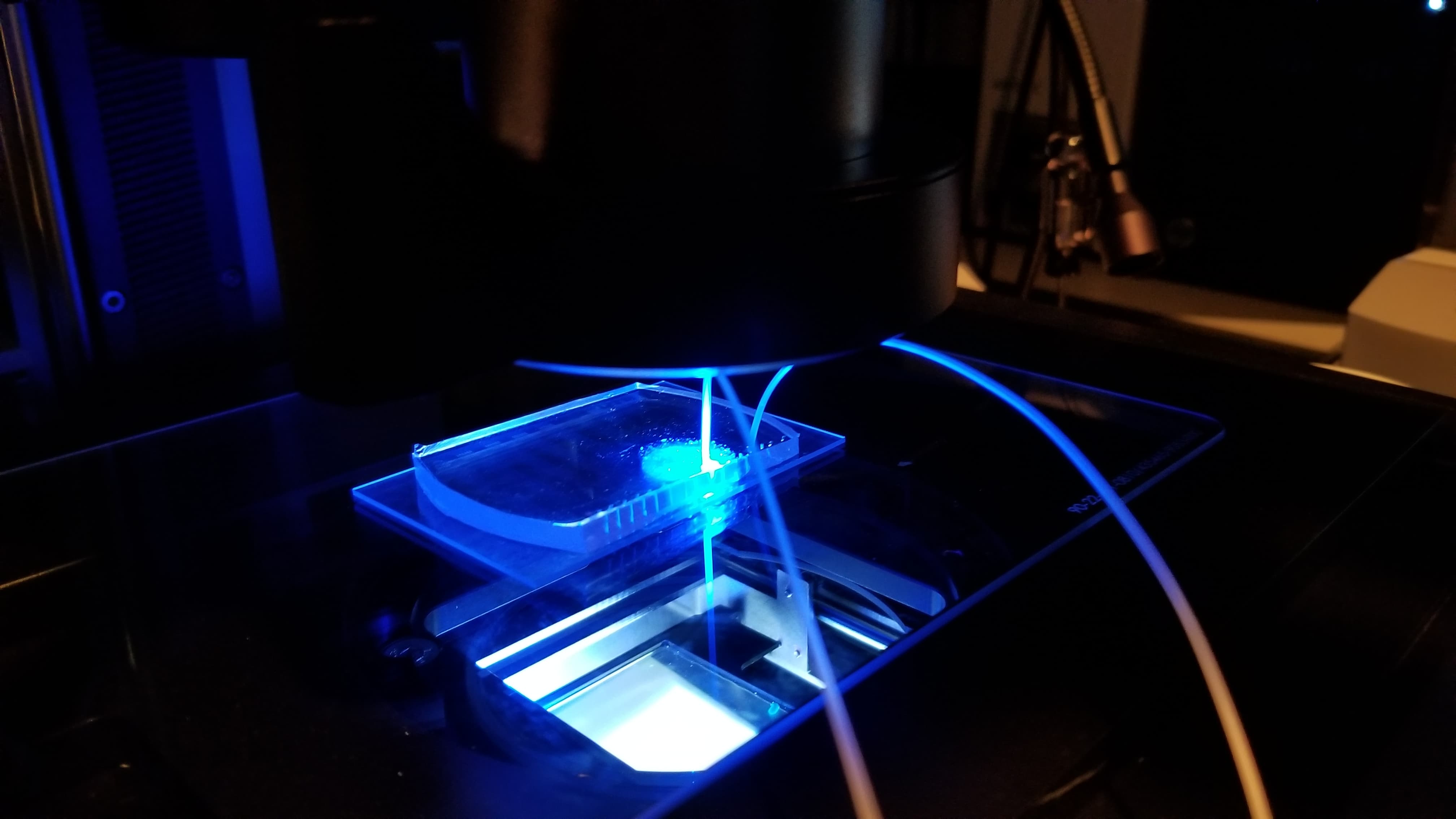

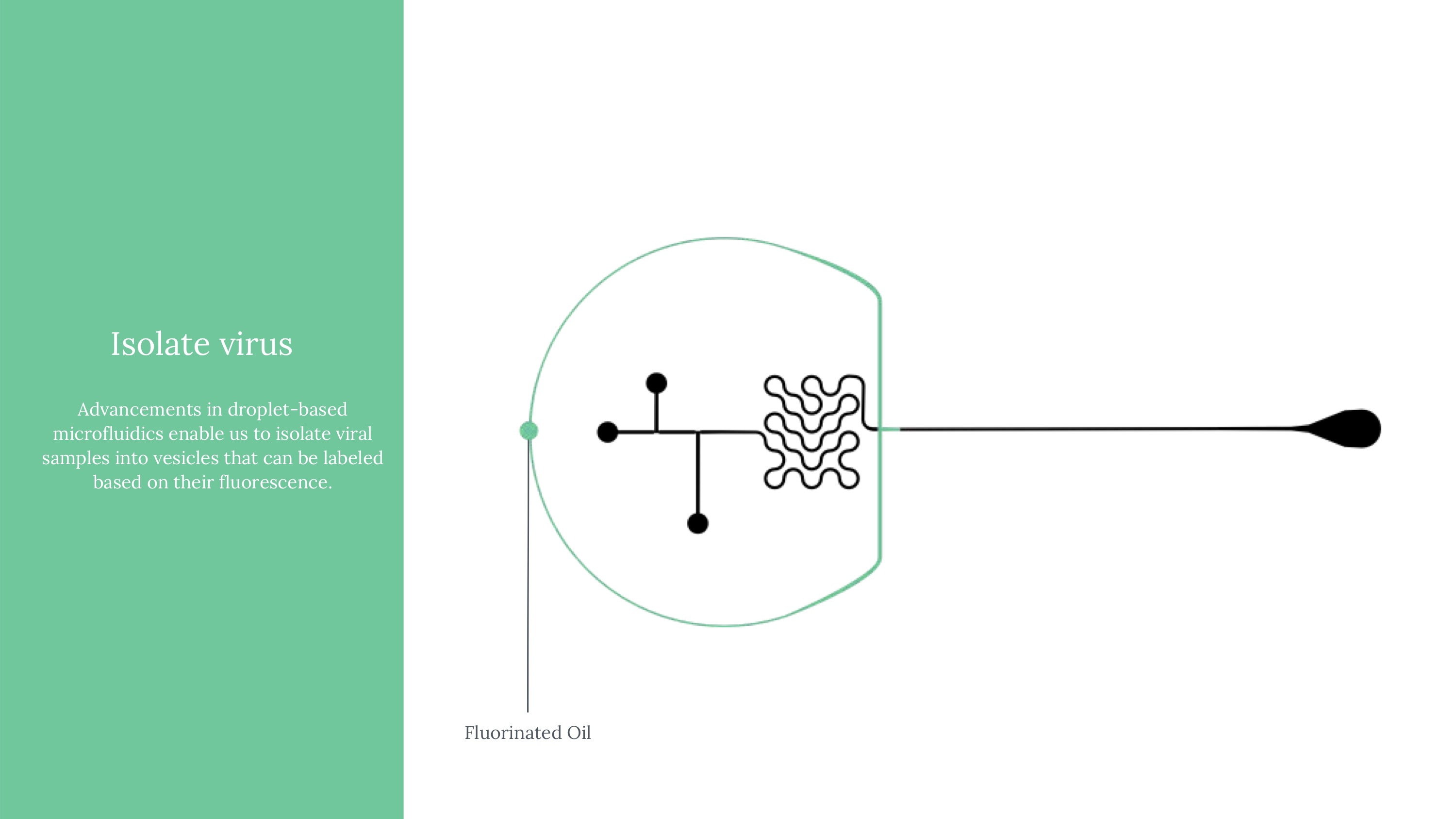

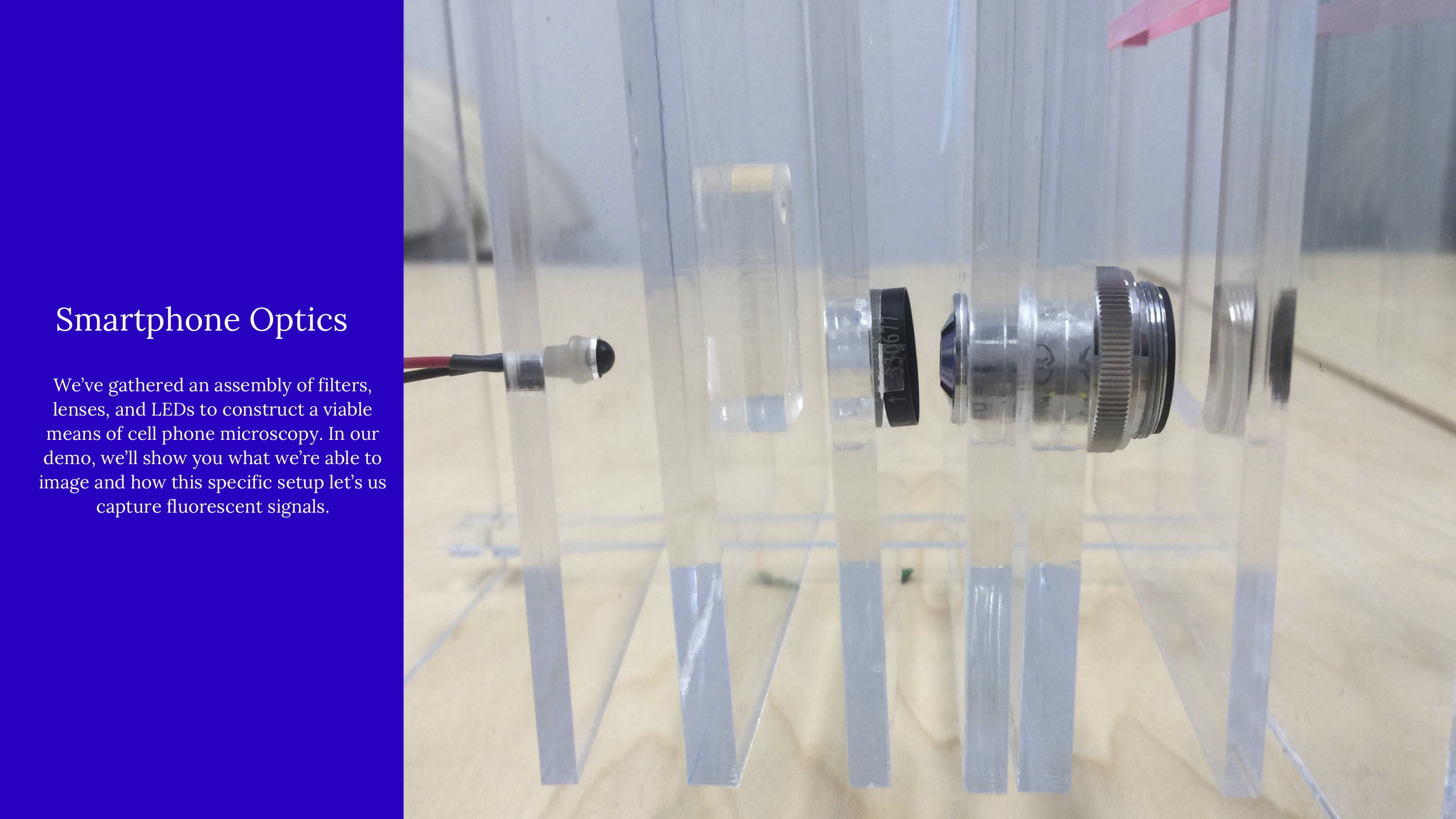

Another critical part of our testing rig was a set up to manage light (which exposes vesicles that contain fluorophores in an excited state). This was functionally our way to mark which vesicles contain the virus, after using flow cytometry to form controlled vesicles. The microfluidic device requires inputs from a few channels - one for a prepared sample, two for different FITC fret pair components, and fluorinated oil.

An early model of the device, some early calculations on flow cytometry and vesicle formation, and images of lab work in progress.

Early on, we used low-fidelity prototyping with laser cutting to engrave channels in acrylic, and actually get a better grasp of flow cytometry, and structures like mixers.

An exploded model of our camera, with filters that could specifically help us capture the emissions from our fluorophores.